|

David Rhodes Archive

|

|

Guitar Player - December 1992

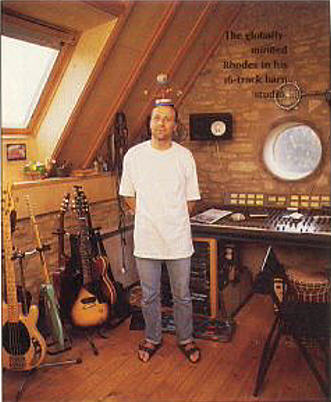

Profile – David Rhodes – Peter Gabriel’s Un-Guitarist by Paul Tingen  “If I can get away with playing one note in a song,” says David Rhodes, “for me, that’s success.” But unlike many “play-for-the-song” players who view restraint as a function of musical superiority, David Rhodes will joyfully send up any illusions you might have about him being a great player. Rhodes gasps when hearing simple fingerpicking licks: “I can’t play those fancy guitar parts!” Peter Gabriel’s guitarist of choice since 1979, the 36-year-old Rhodes has also played on albums by Toni Childs and Joan Armatrading. His latest work is on Gabriel’s new Geffen release “Us”, the first collection of new Gabriel vocal songs since 1986’s blockbuster album “So”, on which Rhodes laid down slinky guitar grooves for the funky hits “Sledgehammer” and “Big Time”. So why did Gabriel hire Rhodes 13 years ago, plucking him from an obscure new-wave band called Random Hold? “I don’t know,” Rhodes exclaims, mystified. “I was suddenly standing in a room with people like [drummer] Jerry Marotta, who were on a level of musicianship 10 times as high as I could ever expect to reach. I still feel like that when I’m in a room with a lot of musicians, because technically I’ve never been any good. What I do well is groove and play the song. In rock music, the most important thing is getting across the mood and the song.” When Gabriel recorded his third eponymous album in 1980 [Mercury], the aim was to use every instrument in a non-conventional way. Rhodes began playing distorted, open-tuned block chords, two- or three-note melody lines, and atmospheric effects that flew in the face of conventional lead and rhythm roles – an approach that has become his trademark. “I share Peter’s attitude of avoiding the obvious,” Rhodes offers, sitting in the attic studio of a renovated hay barn just yards away from the old English cottage he calls home. “It helped that I was completely unable to play the obvious guitar things. I enjoy people who play really well, but it’s the attitude, the way you look at music, which is all-important.” “Us” is much more guitar-heavy than “So”. This shift in direction becomes apparent as soon as Rhodes’ mightily distorted feedback commences on the opening cut, 'Come Talk To Me'. Rhodes credits the record’s sound to producer/guitarist Daniel Lanois (U2, Bob Dylan). “Daniel played a lot of guitar on this album,” Rhodes explains. “He felt the immediacy of the guitar would help the songs. But I don’t think Peter particularly wanted it to be a more guitary record. There are bits of it which are too guitary, actually.” While most of the guitar parts are Rhodes’, Bill Dillon plays on 'Love To Be Loved' and the Meters’ legendary Leo Nocentelli appears on two tracks as well. Rhodes’ main guitars are three Steinbergers: a 12-string, a model with a TransTerm transposing tremolo, and a very early prototype. He also owns a ’62 Fender Jazzmaster (“an old friend”), and a ’66 Gibson 355 fitted with an early-model Sustaniac, a feedback device made by Maniac Music, which mounted on the guitar’s headstock, allows the player to use a foot pedal to determine which harmonics will feed back. A Chet Atkins semi-acoustic, a ’54 Gibson Les Paul Junior, a ’62 Fender Stratocaster, a 12-string Ovation acoustic, and a K. Yairi acoustic with a violin-style headstock round out Rhodes’ collection. David runs his signal through Boss Vibrato, Chorus and Octaver pedals, a T.C. Electronic distortion box, and a master volume pedal. Though he owns a Vox AC30, a Roland JC-120, a 60/100-watt MESA/Boogie, and a small Gallien Krueger, Rhodes often defers to the engineer when it comes to making amp choices: “He knows the room and the sound he wants, so I’m happy to work with whatever he plugs me into.” Preferring the sound of worn strings, Rhodes uses gauges .010 through .046 for electric and .011 through .052 for acoustic. A fan of Chris Spedding, Ralph Towner, Jimi Hendrix and John McLaughlin (particularly McLaughlin’s angular rhythm work), Rhodes quickly points out his own musical priorities. “I’ve never been one for guitar pyrotechnics,” he says, allowing that he prefers to simplify lines rather than tackle complex chord structures and harmonies. “Knowing your limitations is really important, but within that you should also push at the edges of what you can do.” Not surprisingly, Rhodes is ambivalent about guitar solos. “If I’m playing a session, and somebody asks me to play an eight-bar solo, I’ll say ‘Can’t we refer to this as a musical interlude?’ I can’t do the whole spotlight thing.” How has Rhodes evolved as a player during his years with Gabriel? “I can now play some of the horrible things that I was almost proud of not being able to play,” he laughs. “I enjoy playing more. I used to struggle because I was so untogether. Every time I played I was very tense. Perhaps I was a more exciting player then, because when you’re struggling to express yourself, there’s a tension that can be exciting. Today, I’m better at structuring parts, and my timing is better. But overall I still work in the same way I used to, I always play less rather than more, which is difficult sometimes, especially at sessions. People want some of those elements that are the essence of guitar. To distill that essence and at the same time make my playing sound fresh is still my greatest challenge.” |